Three months in Norway with Tukuuludaa: Recap Part 1

- Tukuuludaa

- May 23, 2025

- 8 min read

We are eternally grateful to everyone who made this trip possible, including (but not limited to): ULU of Norway, the Ulakaia Center, Native Movement, Aleut Community of St. Paul Island, Norwegian Handicraft Institute, TDX Corporation, and the Central Bering Sea Fisherman’s Association. It takes a village to manage a project as big as revitalizing reindeer and fur seal crafting on St. Paul Island, and we are thankful for ours.

Aang Tukuuludaa followers!

Last week, we arrived back in the United States after 89 days in Norway. While we had originally planned to stay only six weeks and update you all as we went along on our website, we were not only so busy, but we received additional funding during the trip that made it possible for us to stay longer and participate in more events and trainings, including the Second International Gathering of Northern Seal Hunters and Crafters in Hysvær, Norway, as well as the Annual Meeting of the Norwegian Handicraft Institute (where we met Her Majesty, Queen Sonja), that we simply didn’t have time. We want to share a full recap of our time in Norway, but there is far too much information for just one blog post. Over a few installments, we will share our journey, including: why we went, how we were able to get there, and what’s next for us!

Origins of our Scandinavian Trip Project: St. Paul Island’s Reindeer

Our project starts with the story of Hannah Atsaq and Garrett Iĝayux̂. Before we founded Tukuuludaa, Garrett Iĝayux̂ had begun working on his own with the revitalization of seal-hide tanning and handicraft on St. Paul Island and Hannah Atsaq was living in Norway.

Hannah Atsaq came to St. Paul for a summer job in June of 2024. she had just moved back to Alaska after 3 years in Guovdageaidnu, Norway. Guovdageaidnu is home to one of the largest communities of Northern Europe’s Indigenous Sámi people. The largest industry in Guovdageaidnu and an essential industry for the well-being of the Sámi people is reindeer herding.

During the three years Hannah Atsaq lived there, she saw just how important the reindeer were for the community. Their meat provided year-round sustenance, their pelts became beds on the floor of traditional Sámi lávvo (tent) housing, meticulously de-haired reindeer skins were sewn together into clothing and storage (in addition to a limitless range of other appliances). Antlers could be fashioned into knife parts and utensils. Reindeer legs and head furs made the basis for durable snow shoes. As was explained to Hannah Atsaq by her first boss (a Sámi reindeer herding woman), “the reindeer here are higher than God.”

It was a shock to Hannah Atsaq, when she arrived on St. Paul to learn that there was no culture or knowledge surrounding the tanning, preservation, and/or crafting of reindeer skins, pelts, and antlers. She learned that on this island, people would often shoot the reindeer, take the meat, and then throw the furs, skins, and antlers away. In Hannah Atsaq’s mind, this practice was a waste of valuable materials. She wondered why there was no tradition with reindeer handicraft on St. Paul Island, and even brought it up to Garrett Iĝayux̂. Together, they did some research – and suddenly the answer became clear.

The History of Reindeer in Alaska and St. Paul Island

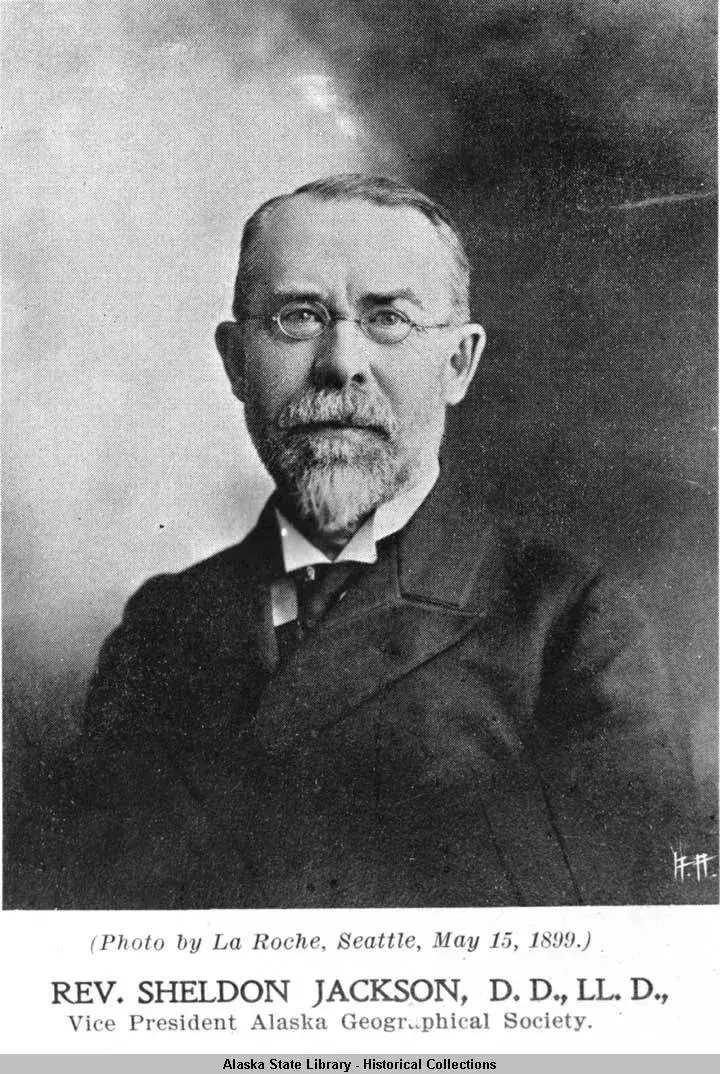

It is important to note here, that reindeer are NOT indigenous animals of Alaska, but rather were brought here during the late 1800s and early 1900s. In the 1880s, Sheldon Jackson, a missionary and the then education secretary of Alaska, traveled between Western Alaska and Siberia building churches and other religious institutions in the region. He also documented the daily lives of and collected traditional items from Indigenous communities during his travels. Jackson was particularly fascinated by the Chukchi community of Siberia, whose traditional livelihood was and continues to be reindeer herding. He began to wonder if such an industry could work in Alaska.

“There are hundreds of thousands of square miles of area within the Arctic regions of Alaska that, there is no question, can never be adapted to ordinary agricultural pursuits, nor utilized for purposes of raising cattle, horses, or sheep; but this large area is especially supported for the support of reindeer.” – Sheldon Jackson, 1891, Introduction of Domestic Reindeer to Alaska.

In 1891, Sheldon Jackson published his yearly Alaska education report, in which he told of natives in Arctic and rural Alaska as “a starving people”, whose only food supply (according to Jackson “whale and walrus”) was “practically destroyed” (Jackson, 1713) [We know now that is not true and Jackson was mistaken about native starvation]. Jackson, as a solution to the supposed starvation crisis, proposed importing reindeer from Siberia to Alaska to establish a reindeer herding industry here. Jackson also wanted to bring Chukchi reindeer herders from Siberia to Alaska as their teachers. Later that year, Jackson and his fellow missionary William T. Lopp brought the first group of 16 reindeer to Alaska. They were placed in the Aleutian Islands.

In 1893, The Alaska Reindeer Service (ARS) was formed under the national Department of Education to formally bring reindeer husbandry training to Northern and Western Alaska. One of the first acts of the ARS was to remove the Chukchi as potential reindeer herding instructors (according to some reports, because they were not christians). The ARS then turned to another group of reindeer herders who they hypothesized could teach Alaska Natives reindeer husbandry and were also christians, the Sámi people of Northern Europe. Later that year, the ARS posted advertisements in Scandinavian newspapers soliciting reindeer herders to come work and teach in Alaska. They received 250 responses.

In 1894, a representative of the ARS traveled to Guovdageaidnu (remember the first part of this blog post – everything is connected!) to recruit (christian-only) reindeer herders. 13 Sámi men and women agreed to three-year teaching contracts in Alaska. They arrived in Teller, Alaska in July of 1894 and began to teach Iñupiat how to “milk, lasso and tame reindeer and how to make cheese, glue, sleds, fur boots, harnesses and other items.” (International Sámi Journal)

In 1897, the first contingent of Sámi in Alaska’s contracts expired. Three Sámi families chose to stay in Alaska and three chose to return to Norway. Jackson, still in charge of the ARS, wanted to expand the program to more communities in Western Alaska, so he got congressional support to bring more Sámi people and their reindeer to Alaska.

In 1898, almost 100 Sámi and 200 of their reindeer arrived at the newly-formed reindeer herding station in Unalakleet, Alaska. Each held a two-year reindeer-husbandry and teaching contract. In 1900, when their teaching contracts expired, 86 of them decided to stay in Alaska and 24 to return to Norway (numbers not adding up to 100? Remember Sámi were also having kids in Alaska!).

In 1899, Norway banned the exportation of reindeer *, and in 1902, Russia followed suit. Alaska has not had any reindeer imports since these restrictions were placed 126 and 123 years ago, respectively.

In 1909, as xenophobia was rising in the United States, the ARS decided they would no longer employ Sámi reindeer herders, instead they would only hire Alaska Natives who had been trained in reindeer herding.

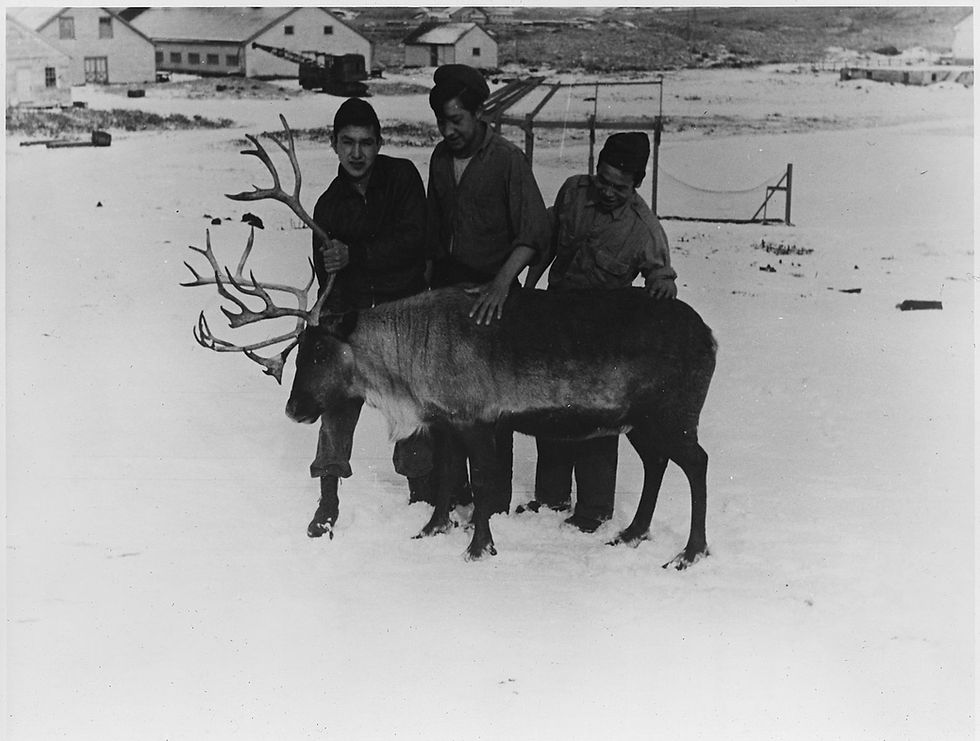

In 1911, 40 reindeer were brought to the Pribilof Islands. 4 bucks and 21 does along with a Iñupiaq or Yup’ik (exact ethnicity/tribe is unknown) herder arrived on St. Paul Island (as Sámi reindeer herders were no longer in the ARS’ employ). Over the next 30 years, the reindeer husbandry industry thrived on the Island, with local Pribilovians taking charge as the government offered them reindeer herding contracts. Garrett Iĝayux̂’s great-grandfather was one such Pribilovian who became a government-contracted reindeer herder. In 1938, the reindeer population on St. Paul Island reached an all-time high of 2,000.

In 1944, Pribilof Islanders were evacuated from St. Paul Island to Southeast Alaska for the duration of World War II. The evacuation brought St. Paul Island’s reindeer and reindeer herding industry to a grinding halt. When the Pribilof Unangan returned to St. Paul island, there were but 240 reindeer left. By 1950, only 8 would remain and the government herding contracts would be gone.

The Sámi, who were once the main source of education for Alaska Native herders, could no longer be a resource as before. In 1937, the US Congress passed the Reindeer Act, banning the Sami and all other non-native Alaskans from herding reindeer (this act still stands today). In connection with the passage of this act, most Sami in Alaska were forced to sell their herds to the government. Most of those Sámi who had not married into Alaska Native families left for Washington state.

As Hannah Atsaq and Garrett Iĝayux̂ learned more, they realized that the tradition of reindeer crafting on St. Paul Island had not been lost, but rather there was never really a tradition to begin with. How could a reindeer culture develop in the mere 30 years when the reindeer herding industry was supported on the island? Especially when all of the knowledge surrounding reindeer was not traditional Unangan, but passed to them through others? How could Pribilof Unangan retain the knowledge they were taught when they were removed from their island just as they became successful reindeer herders? What could Unangan do when they returned to St. Paul the reindeer population was decimated?

Still, the question remained for us, there are almost 1,000 reindeer now on St. Paul Island and approximately the same on St. George. If the skins, pelts, and antlers are not utilized, they become trash. How can we take advantage of this great resource on our island to build a sustainable reindeer crafting culture? To do that, we would need to get some knowledge.

How do we rebuild a century of lost reindeer knowledge? We wanted to return to the site of Alaska’s original reindeer husbandry teachers, Sápmi

Sápmi is the name of the Sámi homeland that spans Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Northwest Russia.

In September of 2024, shortly after launching Tukuuludaa, Garrett Iĝayux̂ got word of a grant opportunity from Native Movement with the theme of Alaska Native Arts. One focus of the grant was to provide sponsorship for artist training among less and more experienced artists and handicrafters. To that extent, we began to reflect on the state of reindeer crafting on the island and what it would take to build a sustainable reindeer handicraft culture. We knew that we would have to go abroad to get that kind of training. But how far?

We thought about how Sámi and Norwegians came to Alaska 120 years ago to teach Alaska Natives to herd and work with reindeer. We thought it was time we go back to them. So, we wrote our grant with an exchange trip to Sápmi in mind to build skills in reindeer crafting that we could bring back with us to Alaska. Luckily, it seemed like Native Movement seemed to agree with our project goals, and in January 2025 we were awarded a Movement Fund grant to go to Scandinavia. Shortly after we received our grant from Native Movement, the Tanadgusix Corporation (TDX) gave us additional funding.

Curious how we planned our journey? Be on the lookout for the second installment of this blog!

*: Norway banned the export of reindeer moss, which was a way to ban the export of reindeer since you cannot export reindeer without a food source.

Interesting reading and new information recieved, thanks.

Interesting...enjoying...to read.....